In my nutrition practice, I take pride and joy in the work that I do. As a weight-inclusive, Non-Diet Dietitian, I see how moving away from weight as an indicator for health not only has improved the rapport and trust with my clients but has led them to feel better in their bodies.

Whether it’s because they are now able to manage their digestive symptoms, reduce their blood cholesterol levels, or because they have made peace with their bodies and are able to strive for wellness without restrictive eating, I truly feel lucky to have found this approach to Medical Nutrition Therapy to be effective.

When I presented at the Weight Inclusive Nutrition and Dietetics Workshop to a room full of Dietitians, Dietetic Interns, and Dietetic Students, I was asked to share how to incorporate a weight-inclusive approach to Medical Nutrition Therapy into dietetics practices. These may be new words to you, so let me provide some definitions before I share with you what I shared with the nutrition professionals and pros-to-be.

Weight-Inclusive Approach to Wellness

Currently, our health and medical systems operate from a weight-centric or weight-normative approach. This means that an emphasis is placed on weight and weight loss when practitioners attempt to help clients strive for health.

A weight-inclusive approach – and this is how I work in my practice – is an emphasis on striving for health, independent or regardless of weight.

This means that weight-inclusive practitioners treat their clients with the understanding (from much research) that weight is not synonymous with health. One popular paradigm used by weight-inclusive practitioners (be it Registered Dietitians, Doctors, Psychologists, etc) is the Health At Every Size® model.

Medical Nutrition Therapy

According to the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND), the organization that credentials over 100,000 Registered Dietitians and other Dietetics Professionals, Medical Nutrition Therapy is (and I paraphrase): Nutritional diagnostic, therapy, and counseling services for disease management performed by a registered based on the specific application of the Nutrition Care Process that involves individualized nutrition assessment and a duration and frequency of care using the Nutrition Care Process to manage disease.

Medical Nutrition Therapy and the Nutrition Care Process do not specifically note that a weight-centric approach should be used, but that is how we are currently trained.

It is possible to achieve the same or better outcome, based on my own experience with clients, to manage disease and improve health markers from a weight-inclusive approach, and this is what I shared with the participants at the WIND Workshop.

Some of the main points we covered may be useful to you as you consider how you would like to be treated by health care professionals.

1. Weight ≠ Health

Our society is under the impression that thin equals healthy and fat equals unhealthy. This is false. There are people who are thin and unhealthy and fat and healthy (and vice versa). You cannot determine a person’s health by looking at the outside of their body. Case in point: There is not one disease that only affects fat bodies. Thin people can get cancer, diabetes, heart disease, and bad knees!

2. We are not in total control of our health

Diet culture will have you believe that 99% of your health is controllable by how you eat and move your body. This is false. According to the CDC, our ability to influence our health is 25%. Other factors include genetics, education, access to health care, social support, and where a person lives. If you are diagnosed with Diabetes, you did not bring it on yourself. In fact, studies show that weight gain is a symptom of Diabetes and not the cause. Diet culture benefits when you believe that you are in total control because you will continue to return to dieting to achieve health or an acceptable BMI.

3. BMI is BS

Body Mass Index, according to researchers, is 51% inaccurate when used as a determinate for health. It does not take into consideration fat v fat-free mass (ie bones, muscle, fluid), differences in gender, and how our bodies differ as we age. In fact, BMI was not designed to be a screening tool for individuals and the categories – underweight, normal, overweight, and obese – were arbitrarily set and then changed by a panel that included two members that worked for the drug company that made weight loss drugs. What I can gather is that certain groups and companies stood to benefit from continuing to use BMI as a determinant of health, regardless of the data that indicates that it misdiagnoses folks as unhealthy based on their size in more than half the cases.

4. “Overweight” and “Obesity” is not a thing

“Overweight” and “Obesity” are terms that equate body size with health, thus these terms pathologize a body size. If BMI is inaccurate the majority of the time, then being “overweight” begs the question, “Over what weight?” If bodies come in all shapes and sizes, and we do not have total control to change our bodies to all be the same size or fit into the “normal” BMI category, then there is no number that will ensure all bodies are healthy. Your body’s weight – it’s natural weight or set point – is reached when intentional weight loss is not being pursued and disordered eating behaviors to reach the weight loss goal (ie binge eating) are not being practiced. As for the term, “Obesity,” it literally means, “eaten itself fat” in Latin. Again, if we have established that bodies come in all sizes, then a large body is large due to genetics, access to health care, where you live, etc, and not from eating. Thus, “obesity” is a misnomer and not a thing.

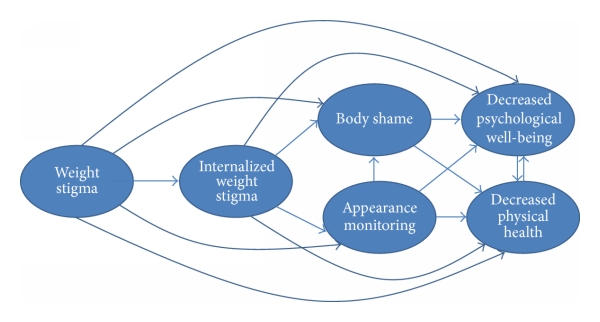

5. Weight-Centric practices can lead to poor outcomes

In a system where body size is pathologized, health practitioners have developed weight bias toward clients in bigger bodies and this stigma contributes to poor health. According to the research, many healthcare providers have negative attitudes about larger bodies, and this stigma impacts their judgment, decision-making, and the care they provide. For those in larger bodies, they feel this bias and its effect can cause high stress, avoidance of care, or poor compliance with health recommendations. There is a saying that goes something like this: Why do we prescribe for fat people something we diagnose as a disease in thin people? This translates to diet and exercise is the first and sometimes the only health recommendation that fat people receive regardless of their symptoms, and for thin people who diet and exercise, we may diagnose them as compulsive, disordered eaters, or having an eating disorder. The “diet and exercise” prescription is negligent and lazy medical and nutrition advice. When we work from a weight-inclusive approach, we can reduce stigma, create a safe space for people in all bodies and treat the symptoms and/or the cause, rather than the size of the body.

I truly enjoyed sharing this information with my peers (and peers-to-be) and my hope is that a weight-inclusive approach to health will be accessible to people like you because there will be more of us practicing from this patient-centered, effective, safe, sustainable, and compassionate place.